Written by: Matt Baran-Mickle

Be sure to check out Part 1 and Part 2

Metabolism and Immunity

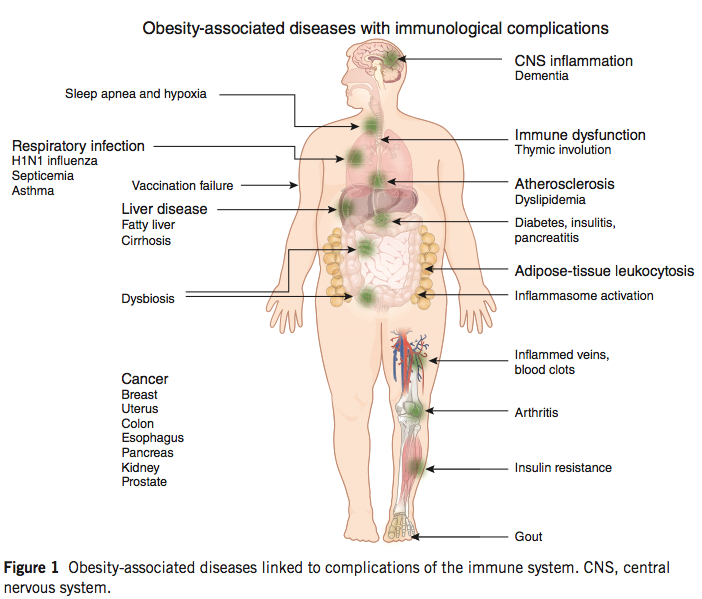

The obesity epidemic is widely recognized, and while the precise causes are not entirely clear, the presence of excessive nutrient intake and subsequent systemic metabolic dysfunction is not controversial. Obesity is frequently accompanied by a variety of conditions that are collectively referred to as the metabolic syndrome, including high plasma glucose, high plasma fatty acids/triglycerides, hypertension, and insulin resistance; immunological alterations in obesity are increasingly recognized as well, and the presence of chronic inflammation is a hallmark of the condition.

These immunological alterations are quite pronounced, and include the accumulation of activated lymphocytes and innate cells in obese fat tissue, and a depletion of Treg cells, as well as mucosal barrier disruption and dysbiosis. Recent work has begun to unravel the interrelation of immunity and metabolism, and provides some intriguing evidence for our developing understanding of autoimmune disease.

Like every other cell, leukocytes require energy and metabolic substrate to maintain normal cellular function, and to divide and proliferate. The metabolic requirements of dividing lymphocytes are particularly pronounced, and their activation is accompanied by a switch to almost exclusively glycolytic metabolism, which allows for the production of metabolic intermediates that are required to generate amino acids, lipids and nucleic acids for the generation of new cells during an immune response. On the other hand, non-activated lymphocytes and Treg cells rely primarily on oxidation, and are non-proliferative.

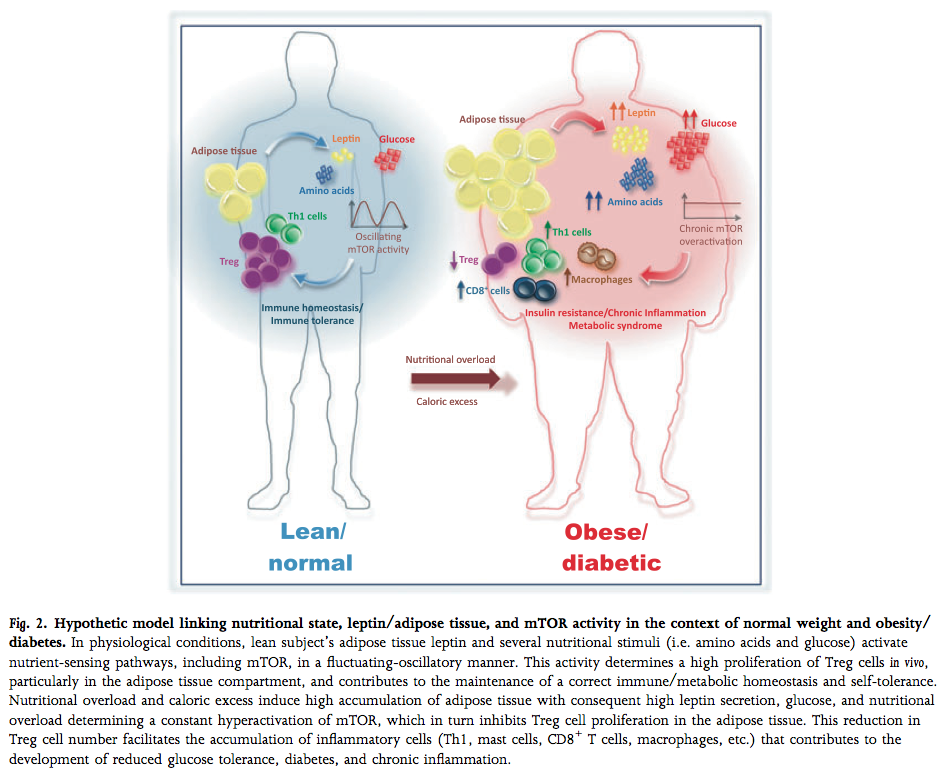

Lymphocytes rely on intracellular and extracellular energy-sensing pathways in order to determine the proper response to a given stimulus, and fat cells provide signals to this effect via the hormones leptin and adiponectin, which signal energy sufficiency/excess and insufficiency/deficit, respectively. Leptin secretion increases in proportion to fat mass, while adiponectin is secreted in inverse proportion, and both act strongly on lymphocytes to elicit specific responses.

In lean fat tissue, adiponectin secretion far outweighs leptin output, and in response, leukocytes in fat tissue are primarily tolerogenic Treg cells and non-activated leukocytes that rely on oxidative metabolism. In obese fat tissue, on the other hand, leptin production predominates, and the presence of glycolytic, activated, inflammatory lymphocytes is dramatically increased.

(image: Matarese, Procaccini, & De Rosa, 2012; mTOR is a molecule inside the cell that caries out leptin signaling)

The presence of activated lymphocytes in fat tissue is surprising, given that activation is dependent on recognition of an antigen and subsequent stimulation. In recent years, the hypothesis that these cells recognize self-proteins in obese fat tissue has gained credibility, and the very recent discovery that fat cells can participate in immunity as members of the innate immune system by activating T cells makes a strong case that obesity is, in fact, an autoimmune disease.

In the presence of excess energy (i.e. the high circulating levels of macronutrients found in obesity) and permissive signaling through energy-sensing pathways (i.e. leptin), inactive, self-reactive T cells can make the switch to glycolytic metabolism and proliferation, allowing the generation of an autoimmune response; the depletion of Treg cells and a loss of adiponectin secretion compounds and permits this aberrant activation, and could potentially be a key mechanism in the generation of autoimmune disease in the rest of the body. In this way, there is a clear line of evidence connecting chronic over-nutrition and the development of autoimmune disease.

Conclusion and Perspectives

We have seen how multiple pathways may contribute to the development of autoimmune disease, and that these act, potentially, through the disruption of energy homeostasis and mucosal immune function. A lingering issue in the discussion of dietary influences on autoimmunity is the order of events; inflammation can drive metabolic dysfunction, alterations in intestinal permeability, and dysbiosis, so causality could lie in any of these directions, or originate from some other source entirely.

The unifying factor in the discussion is a loss of tolerance to self tissues via the generation of inflammation, and multiple roles of diet in driving the development of an inflammatory environment. Evidence for the metabolic effects of immunity on the loss of tolerance suggest that over-nutrition may be a crucial component of this process, and could effect the mucosal barrier, as evidenced by the presence of dysbiosis and intestinal permeability in obese patients. Bioactive compounds in cereal grains, like gliadin, provide a source for the initiation of intestinal inflammation, while a lack of fiber and other potentially disruptive nutritional behaviors can drive dysbiosis. Taken together, this evidence suggests that the modern nutritional environment can promote inflammation and the initiation of autoimmune disease, and increasing research interest in the direct impacts of nutrition on autoimmunity may soon provide dearly-needed evidence to support a true mechanistic understanding of the causal relationships at play.

Image credits:

Kanneganti, T.-D., & Dixit, V. D. (2012). Immunological complications of obesity. Nature immunology, 13(8), 707–12. doi:10.1038/ni.2343

Matarese, G., Procaccini, C., & De Rosa, V. (2012). At the crossroad of T cells, adipose tissue, and diabetes. Immunological reviews, 249(1), 116–34. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01154.x

Matt Baran-Mickle graduated from Hampshire College in 2013 with a BA in Human Physiology and Immunology, completing a senior thesis investigating the connections between nutrition and autoimmune disease from an immunological perspective. He completed pre-med requirements during his undergraduate work, and hopes to pursue a degree in Naturopathic medicine beginning in 2015. In the meantime, he eats, trains, and works in Boulder, CO.

A stellar series of articles Matt – congratulations on the presentation which helps to organise our framework of the possible chain of events of energy overload, immune dysregulation and subsequent disease . It is so helpful to have it all brought together in one document!

so everything starts with overnutrition, interesting 🙂

>> the presence of excessive nutrient intake and subsequent systemic metabolic dysfunction is not controversial

of course it is controverial! some well known researchers would claim that the metabolic dysfunction is what causes insuline resistance, excess fat accumulation, excessive nutrient intake, obesity, etc.

>> Evidence for the metabolic effects of immunity on the loss of tolerance suggest that over-nutrition may be a crucial component of this process, and could effect the mucosal barrier, as evidenced by the presence of dysbiosis and intestinal permeability in obese patients.

And how about the multiple examples provided by Taubes in his books about populations that were undernourished and still managed to develop insuline resistance, obesity, autoimmune problems?

Thanks for reading and commenting Martin – I didn’t go so far as to say that everything starts with overnutrition (check out the conclusion section again). I make the point that overnutrition may be one factor in a complex system involving intestinal barrier function, symbiosis/dysbiosis, and immunometabolic dysfunction, and that all of these can (and do) influence each other. As far as the controversy surrounding the presence of overnutrition in obesity, I defer to you if you have more experience with the literature, as I didn’t have the time to focus much outside of the field of immunology (which might make my statement a little strong), but I’ve never seen anyone claim that overnutrition wasn’t at least *involved* in the big picture, as a symptom, cause or otherwise. It’s not difficult to imagine a situation where inflammation from another source leads to hypothalamic leptin resistance which then leads to at least moderate overnutrition (or something similar), but we really have no idea what follows what at this point. The point about Taubes is well taken, but I don’t suggest that my version of events, as it were, explains everything – just trying to contribute some new ideas to the discussion of obesity and immune function.

That being said, I do truly appreciate your comments, it can be easy to get stuck in a bubble with stuff like this.

Thanks for your response to my comment! I realize the whole picture is pretty complex and things appear not to work in exactly the same way for all people.

Wow! I hope the world is ready to hear that obesity as an autoimmune disease. Good stuff!

Matt,

Doesn’t the existence of metabolically healthy obese individuals indicate that something other than obesity itself is the root cause of this inflammatory cascade? Ie, something other than excess energy intake?

I think those folks are just dealing with the situation in a different way.

Robb, I remember your argument that sepsis, accute inflammation due to bacterial infection, will cause immediate insuline resistance.

Are there any doubts that insuline resistance will lead to excess fat accumulation? The mechanism seems to be pretty well understood. In which case, wouldn’t we end up with a chain of events: inflammation -> insuline resistance -> obesity.

Or would we rather believe (as some do) that obesity causes insuline resistance which in turn causes sepsis and bacterial infection at the end? 🙂

I know of course, that people with sepsis won’t have enough time to develop obesity.

Martin, from my perspective (immunological) obesity is, by definition, an immunometabolic disorder, so the presence of metabolically healthy obese people isn’t really possible; keep in mind that this perspective would require a more stringent definition of “metabolically healthy” that doesn’t include all people without frank disease.

The tough part in all of this right now is determining a hierarchy of influences between the established suspects, i.e. dysbiosis, compromised gut barrier integrity, metabolic dysfunction, and chronic inflammation, because, as discussed above, they can (and do) all influence each other.

I also think there IS doubt that insulin resistance leads directly to excess fat accumulation, as there are plenty of non-overweight folks with metabolic dysfunction (e.g. pre-diabetes). A question to ponder: if insulin resistance makes it more difficult for cells to access circulating glucose/fatty acid stores (and it does), how would insulin resistance enable adipocytes to accumulate excess fat?

Fascinated by this stuff!

Isn’t it possible that some cells become insulin resistant while others don’t? As in, if/when the muscle cells become resistant, the adipose tissue continues to suck up glucose like a champ and convert it to triglycerides for storage.

Peter Attia addresses this pretty nicely in his TED Med talk (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3oI104STzs). He suggests that obesity is a kind of protective mechanism. The body, in its innate wisdom (or genetic hard wiring, whichever way you prefer to look at it) squirrels glucose away (as fat) in the adipose tissue instead of overflowing the rest of the system with even more glucose and all the sequelae that would lead to: more glycation, more oxidation, even more severe mitochondrial dysfunction and overall havoc at both the cellular level and the level of the organism (human body) as a whole.

It’s a beautiful idea. Seems like there’s a lot of species-wide variability, because, like you said, there are plenty of insulin resistant/metabolically malfunctioning people who are NOT obese. So clearly, if IR *does* lead to obesity, it doesn’t do so in *everyone.* And people can become obese for reasons other than IR. (Usually some other hormonal reason, like thyroid, or dysregulation somewhere else in an endocrine cascade.) And we also know pretty well that obesity is only one consequence of insulin dysregulation and improper metabolism of carbohydrates. There’s Alzheimer’s, T2 diabetes (in the NON-obese), heart disease/vascular complications, even early aging, etc.

There’s more and more talk about personalized medicine via genetic testing in the future. I think (or hope) that might lead to a better understanding among the general public that leanness doesn’t automatically imply good health. And I think it will also shed light on the possibility that genetics is a big player in the *RESULT* of insulin resistance in any given person. That is, why does Joe get fat from carbohydrate intolerance, while Mike remains lean but has Alzheimer’s and an A1C of 9? The same underlying imbalances will have different end manifestations, and I think *that’s* where the genetic factors come into play. (I could look at my family as an example…most of the older people are obese and some have T2D, but all tend to live into their 80s and 90s with good cognitive function. Crazy to look at it from this perspective, but you can see Dr. Attia’s point of view — that even with all its own problems, when it comes down to brass tacks, in terms of straight-up survival, obesity is potentially a safer/better alternative than allowing more glucose to flood a system that is already drowning in it. Obesity as a failsafe…it’s a neat idea, even if the average layperson in our thin-obsessed society would have a really hard time understanding that.)

Amy, I totally agree with your take on this, awesome summary!