Written by: Kevin Cann

October is a busy month for us. From a competition schedule perspective. We put on a meet with RPS October 8th and 9th, and that Thursday I fly out to Atlanta for USAPL Nationals. Due to these dates rapidly approaching, I have had the same conversation with a couple lifters regarding how volume and intensity affect us, how a taper works, and to relax and trust the process.

What I realized was that not many coaches understand how to apply the scientific principle of overload to proper programming. This process is not as simple as people make it out to be. Basically, the overload principle states that we need to stress our system out by doing more than it is capable of, recover so that it adapts, and then come back and do more.

Hans Selye identified the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) in 1929. This states that we need enough stress to force the body to adapt, too little stress will not lead to adaptation, and too much stress will lead to injury. Every system in the body reacts differently to the stress applied and all of these systems respond differently to volume and intensity.

Our fuel system, nervous system, hormones, and tissues all respond differently to training. They are all affected differently from volume and intensity as well. Fuel stores tend to recover pretty quickly as long as we are eating appropriately. We need enough carbohydrates to fuel training and enough fats and protein to aid recovery.

On the other hand, our tissues take longer to recover from training. There have to be enough light days/weeks thrown into the program to make sure that this system does not accumulate so much fatigue that we actually get hurt.

Too much high intensity training will fry our nervous system, and not enough will not allow us to develop the stability and strength required to lift heavy weights. Too much volume and intensity (volume being more important) can lead to a drop in our anabolic steroids like testosterone and a rise in our catabolic hormones such as cortisol.

We need to train above our threshold, but not so far above that we can’t recover. This is different for everyone. Genetics plays a role, as well as training age, recovery (diet, sleep, stress management), and technique. The better our technique, the less energy expended to move the weights.

The exercise and muscles used also affect fatigue. A deadlift is more fatiguing than a squat because the hamstrings have more type 2 muscle fibers than the quads, and type 2 muscle fibers produce more force but take longer to recover.

Also, the closer we train to failure, the more that fatigue accumulates. Often times I will see people in the gym performing AMRAP sets, or even sets of 3-5 reps, but using a weight that they may have 1 rep left in the tank. As we get more fatigue, technique gets worse (which then more fatigue accumulates). From my time training with Sheiko it has been drilled into me that technique is the most important variable.

I have also seen the other end of the spectrum where a workout of the day calls for men to deadlift 135lbs and women 95lbs. For the majority of people these weights are far below the overload principle for intensity. We need enough volume and enough intensity.

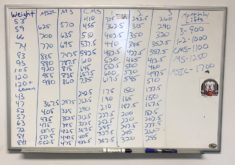

So where do we start? I use the Russian Strength Classification Chart. This chart categorizes lifters based upon weight and total. The lowest rating is a class 3 lifter. This would be a novice lifter and the recommended volume is 900 lifts per month. Class 1 and 2 are lifters would be competitive on the local level and their recommended volume is 1000 lifts per month.

Next level is a Candidate for Master of Sport. Recommended volume is 1100 lifts followed by Master of Sport at 1200. A master of Sport is someone capable of winning at the national level. Lastly, on the chart is Master of Sport International Class. Recommended volume is 1700 lifts and they are competitive at the world level. There is a World Champion category, but no volumes are given. Keep in mind these volumes are counting every rep performed with 50% of 1RM and higher. Below is a picture of the chart from the whiteboard in my office. Find your weight on the left and your total on the right. Weights are in kg. This is your classification.

These volumes are not written in stone, but are more of a starting point. Pay attention to performance in the gym as this is the best indicator of a volume that is too high. Out of these lifts, for novice to intermediate lifters, 20% should be competition lifts and 60% should be competition lift variations. The remainder is your GPP work. Depending on the sport, those numbers can change. A more advanced lifter will do less variations and more competition lifts.

Once your volume is decided, we need to break this up over the training period. I do everything in 4 week blocks to keep it simple. If we train 4 days per week there are 16 training days in one block. We take our total volume and divide it by the number of training days. With 1000 lifts in a month we get 63 lifts per training day. This is the average day. We can add 10% or more volume to given days to make them higher volume days and subtract the same for lighter days.

As volume increases intensity decreases and vice versa. We want to make sure we have enough heavy days in there mixed with lighter days for recovery. Remember that volume builds up the most fatigue and is most important in letting it dissipate.

We then need to look at our week to week training. We want some weeks to be heavy and some to be light. Less than 20% of total monthly volume in one week is a small week, 21-30% is a medium week, and anything over 30% is a high volume week. A month may look like 35% for week 1, 15% for week 2, 20% for week 3, and 30% for week 4.

In the above scenario, the light week followed a higher volume week. I do not like the term deload, as I believe this puts the wrong idea in people’s minds. They think deload and do not put forth the same effort as they would the other weeks. Also, in these lower volume weeks the intensity of the lifts will rise. This way we can make sure we are doing enough volume to build muscle mass and technique, and enough intensity to build more muscle, stability under heavy weights, and the nervous system’s ability to generate max force.

Another way to avoid being overworked is with exercise selection. We do not necessarily have to increase bar weight to increase intensity. We can use accommodating resistance such as bands and chains, as well as pauses in the lifts.

For example, day 1 might be a lighter day where we work on technique stuff in the squat. Sets and reps are 5×4 at 70% of 1RM. We then may come back to the squat at 70% for a 5×4 with chains added to the bar or perform a 2 sec pause at the bottom of the lift.

As intensity increases we can alter the lift to avoid unwanted stress on our joints. We can use a board for board press on the bench and pull from blocks. In a program this may look like a 3 sec pause on the bench for 4-5 sets of 3 reps at 70-75%, followed by some squats which allow the bench muscles time to recover (as well as more volume), and coming back to a 1 board press for 3 singles at 90%.

On a 4 day per week plan you can bench 3-4 days per week, as this is the easiest lift to recover, squat 2-3 times, and deadlift 1-2 times. In my program I bench 3-4 days per week, squat 2, and deadlift 2. With squat and deadlift, one of the days tends to be more technique based with lighter weights, and the other tends to be more geared towards developing strength (although there is quite a bit of overlap for the 2).

The majority of strength work should be done in the 70-80% range. Technique and hypertrophy work can be done in the 60-70% range, and there should be some emphasis on lifting heavier weights between the 80-90% range (especially during the peaking cycle). Volume needs to be high enough to stress enough to adapt, but not too high that we cannot recover.

To ensure we are not accumulating too much fatigue, make sure there are light days and lighter weeks put into the program. Remember that volume is the number one factor in accumulating fatigue and intensity is more important than volume to maintaining strength. Lighter days/weeks should be lower in volume and higher in intensity to maintain strength while recovering from fatigue. It is ok to throw an extra rest day in there as well.

Listen to the signs and symptoms of knowing when to have a rest day and when to go lighter. If performance is declining, you are overly sore, do not feel like training, and sleeping poorly, you may need to look at what you are doing and take a step back.

Getting stronger is hard work. You need to push yourself. Make sure the weights are heavy enough and make sure your volume is high enough. Doing the bare minimum will keep fatigue down, but it will also keep your strength down.

Join the Discussion