Written By: Kevin Cann

If you have not read my previous article about programming, please do so here. In this article I am going to answer a couple of questions I have gotten after people finished reading it. These were some very good questions and definitely add to the information presented in the first article.

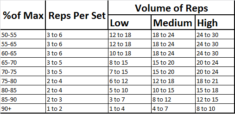

The first question I am going to answer is “How does this volume relate to Prilepin’s chart?” For those of you that are unfamiliar with Prilepin’s chart, it is a guideline of sets and reps to be performed at different intensities as seen below.

This chart was developed by Alexander Prilepin who was the USSR weightlifting coach from 1975-1985. He was not only a coach, but a researcher as well. He looked at technique as well as the speed of the lift and determined that there were optimal volumes that the weightlifters should be working at.

20 years later Louie Simmons brought the use of Prilepin’s chart to the powerlifting scene. It has been used as a powerlifting volume bible of sorts ever since. I use Prilepin’s chart, but as a guideline and not as an absolute. Just hear me out.

First, Prilepin’s chart was developed by researching weightlifters. Bar speed is much more important as an indicator in weightlifting than it is in powerlifting. The squat, bench press, and deadlift are performed at much lower speeds than the clean and jerk and snatch.

You may be asking yourself “but don’t we want to move the bar at max speeds to lift the most weight in the squat, bench press, and deadlift?” The answer is: not exactly. Weightlifting is fast power, but powerlifting is slow power.

We want each repetition of the weight, whether there are light weights or heavy weights on the bar, to look exactly the same. If we move too quickly in the squat, bench press, and deadlift, the chance of altering bar path is high. If the bar travels in a different path for lighter weights than it does for heavier weights, then we are not training to succeed under the heavy weights, as the lighter weights become a different movement all together. There should be no abrupt motions, but instead a powerful and smooth lift.

Movement velocity may be important in weightlifting, but it is not important in powerlifting. What we want from the lifter under maximal weights is maximal intent to move the weight. If we pick lighter weights to move fast, we run the risk of decreasing weights below that of the overload principle that I discussed in my first article. This is one reason that I choose to use bands and chains at heavier weights than what is required from the speed work popularized by Westside Barbell.

Moving with maximal intent develops the nervous system and muscle fiber development of the muscle without violating the overload principle. Remember that in order for us to develop strength the majority of our lifts need to be done between 70% and 80% of 1RM, with some heavier weights thrown in between 80%-90% of 1RM occasionally.

Back to the use of Prilepin’s chart. With all of that said, I do use it when writing programs, but as a guide and not written in stone. We can occasionally increase reps for each set in powerlifting compared to weightlifting because speed is not as important and technique is not as complicated. Occasionally hitting sets of 8-10 on the lifts has its place. For example, Sheiko will very occasionally have me perform a pyramid that might be done at 70% of 1RM for a 3+7+2+8+4+9+6. The sets with 7, 8, and 9 are higher than suggested by the chart as well as the total volume.

It will also make it very hard to hit the total amount of volume required in your training if you adhere to the chart strictly. However, if there are 2 squat sessions in one training day, we can use Prilepin’s chart for each one. For example, the first squat may be 65% of 1RM performed for 5 sets of 4. We may then go bench and come back to another squat session where we perform 4 sets of 2 at 80% of 1RM. The total for the day would be more than the optimal volume listed in the chart, but each session would fall within the guidelines.

60%-65% of 1RM is technique work. The intensity of the lift is too low to develop maximal strength, and if we start trying to move more quickly, chances are our technique work is now being done with poor technique that does not mimic the competition lift with heavy weights. The benefit of a training day such as this would be for recovery, as this would fall under a lighter day as long as the volume is kept on the lower side.

The other question that I received was “What if I am not competing in powerlifting, but want to get stronger for another sport?” This is a great question. The same principles apply to getting stronger no matter who you are and what sport you play.

The first step in this process is to look at your schedule and mark every practice and competition on it. It is even better if you can mark the practices as light, medium, or heavy days. We now can fill in the spaces between with training days.

We want to make sure that our light, medium, and heavy training days line up well with our practice and competition schedule. We do not want a heavy day in the gym right before a major competition. Choosing volume is the next step in the process.

If you have experience with the lifts, I would recommend cutting the total volume recommended by my previous article by 1/3. This may need to be cut even more depending on the sport and whether you are in-season or not. A good starting point is 700 lifts in a month.

From here, everything is the same as the previous article. Divide that number by the number of training days, and follow the rules of light, medium, and heavy days. Once the volume for those days is decided, you just plug them into the calendar. Track your intensity, volume, and progress and continually increase it over time.

I like the use of double squat sessions (more so than bench and deadlift, although I do use those sometimes as well) for athletes. Athletes are required to be strong late in games when fatigue has set in, so why wouldn’t we want to train this in the gym? This gives them the tools and confidence to be strong late in a game.

Programming to get strong is not as easy as some people like to make it out to be. If anyone has other questions please feel free to reach out and ask. Hell, I even have questions from time to time.

Join the Discussion